We are in Lubumbashi, a bustling city at the southern tip of DR Congo. Vic and I lived in Lubumbashi for two years forty years ago. He taught chemistry at the university and our daughter was born here. Yesterday we hired a taxi driver as our chauffeur for the day and went to visit the university and other places.

Verno Masheke, a student and son of our friend Pastor Birakara, Vice President of the Congo Mennonite Church, had agreed to meet us at the Faculté Polytechnique and show us around. That was the building where Vic had taught chemistry in a steeply sloped lecture hall and laboratories with no running water most of the time. We had carried a package the size and weight of a small ham for Masheke from his mama in Tshikapa.

Masheke showed up with two other students, one of them a young man named Junior who asked us for the letter his mama had sent with us from Tshikapa. I had forgotten all about it. On our last day there at least a dozen letters were thrust into my hands, most destined for people in the US, some with addresses and others that would require some research or one more courier to reach their destination. But I remembered getting Junior’s letter, and his mother putting some cash into it before she sealed it. So when I apologized for forgetting it, I could understand why Junior’s face fell. I promised to go back to our lodging, get the letter, and give it to Masheke before the day was out. (I found it, stuck in an odd folder, after a frantic search.)

But before Masheke and friends arrived at Polytechnique, a man monitoring the entrance assured us we were expected and took us to the third floor, to the office of a man wearing a neat white African shirt, dean of Polytechique. He seemed puzzled to see us and not too interested in finding out what brought us there, although we told him the story that we would repeat a dozen times throughout the next hours: Vic had been a professor here 40 years earlier, we were coming back for a visit, we wanted to look around.

We decided to go back downstairs and wait for Masheke. After he arrived he began taking us on a walking tour of the campus. Masheke didn’t know the main campus too well because his classes in pharmacology were in the center city, but we made our way around, accompanied by John, our driver, who was not interested in waiting in the car and seemed interested in learning what he could about the university. I took a few pictures with my iPad.

School wasn’t yet in session for the year but there was plenty of activity around student quarters. I decided to take a picture of one of the open-air computer and photocopying centers you find in many places, an enterprising Kinkos-type operation on the veranda of a dorm. Since I wanted to take the picture from relatively close, I asked a well-dressed man working there whether he minded. He said that it wasn’t up to him; I would have to get permission from the authorities to take any pictures at all on campus. He told Masheke which office to take us to.

Vic wondered whether I wanted the picture that badly and I said, yes, I had seen these photocopying operations in Kinshasa and knew I couldn’t take any street pictures there–partly because of translator Azir’s resistance to anything that might get us into trouble–and this was my chance.

The person to whom we were directed listened to our request and then sent us to another office in a different building. This person, after listening to my spiel, told us to follow him and accompanied us to a third office in another building some distance away. It was at the other end of a corridor through one-story rows of student rooms, redolent of woodsmoke and fresh sewage. I resisted the urge to take pictures.

It was explained that the student “city” for the 5,000 on-campus students (the university has 25,000 students in all) had two dorms for women and nine for men. These one-story rows were clearly guys’ quarters. Our later guide told us this corridor was called Che Guevara Boulevard because all the school “revolutions” or student unrest started here. He assured us they hadn’t had any of that for a while.

We finally reached Bureaucrat Number Three, who assured us that, if it were up to him, we could certainly take pictures, but, alas, it was not up to him. We would have to talk to the Academic General Secretary (dean) in the main administration building, which was a mile down the road from the campus.

I thanked him and we left his office. I was ready to give up at that point. When I told the second bureaucrat, who was still with us, that we would just have to forget about it, he pointed out that I should then go back tell Number Three that he should not expect a call from his superior, because surely Number Three would be waiting for it. Vic was game to continue the quest, now that it had gone on this long, and so we got into the car and headed to the administration building.

As we went up the stairs in the building to the fourth floor (and then back down to the second because Masheke got the wrong office at first) I recognized the first spot in Lubumbashi that brought back memories. It was the glass block–walled stairwell. Many of the glass blocks were broken back in the early 1970s. Back then several had round bullet holes in them from the “troubles” of the 1960s post-independent violence, the abortive secession of Katanga Province, where Lubumbashi (then Elizabethville) is located, and a series of those student “revolutions.”

The bullet holes were still there. Again, I resisted the urge to take pictures.

At last we got to the spacious office of Professor Nkiko Munya, the academic dean, a man in his late fifties or early sixties, who greeted us warmly and told us that he thought Americans were pretty much responsible for all of the violence in Congo. We then had a lively, friendly conversation. We did not disagree that Americans had a hand in everything from Patrice Lumumba’s assassination to the current conflict with Rwanda, though we pointed out others were involved as well. And we pulled out our pacifist Mennonite credentials, told him we were with the son of the Vice President of the Mennonites in Congo. Professor Nkiko had never heard of Mennonites. Later Masheke pointed out a half-built church on the edge of campus, in the section given over to chapels, that was being built by the Mennonite Church.

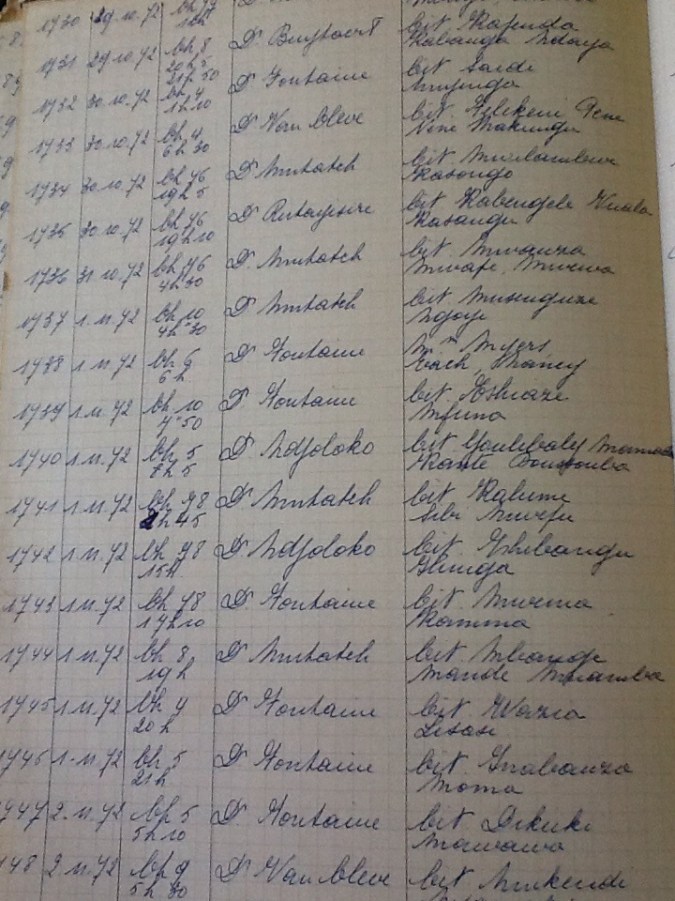

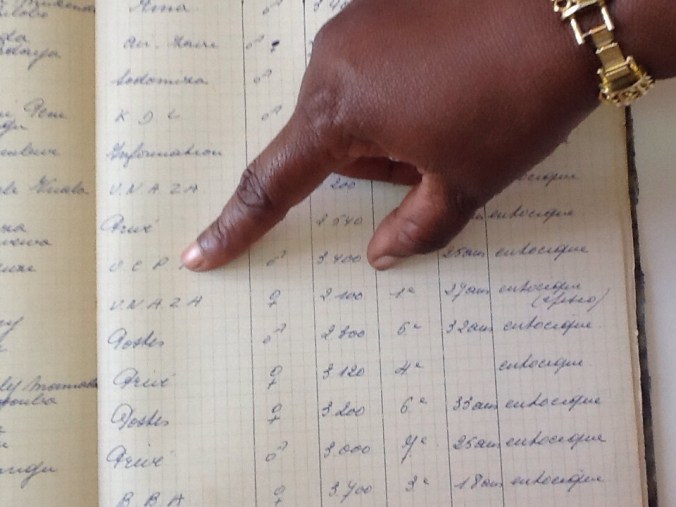

We touched on old times. Nkiko had graduated from the university a year before we arrived. He was from North Kivu and had attended the Catholic high school in Bukavu where I taught English in the year we lived there. That was a Jesuit school dedicated to producing a new, educated elite, as Nkiko had turned out to be. We reminisced about the nationalization of the three main universities that took place just after our arrival, which had prompted our reassignment from Bukavu’s Institute of Mines to the Lubumbashi campus of the new National University of Zaire, or UNAZA.

In the end, Nkiko agreed to let us take pictures on campus and, to make sure we got a good tour and didn’t get into trouble, he assigned his assistant, a smooth-faced young man named Didier, to accompany us. Didier drove a Mercedes up to the main campus and invited us to park the taxi and join him in the Mercedes so he could give us a better tour.

And it was a better tour. We went back to Polytechnique and this time were shown laboratories and classrooms. (We said hello again to the dean, who didn’t seem any more interested than the first time.) The building was bigger and fresher looking than it had been in the 1970s. It had been enlarged and appeared well-maintained. We met a laboratory instructor named Simon who had been around shortly after our time and knew an American professor who had been a good friend of ours and who had stayed longer than we had. Thus we continued to graze connections with the past. Simon told us that the labs still didn’t have running water much of the time.

We saw buildings that were in rough shape and others that had been spiffed up. Unlike the Christian University of Kinshasa, which we had visited early in the trip, the University of Lubumbashi looked like a university.

At the end of the tour I asked to go back to the student Cité and photograph the “Kinkos”. As I was taking the picture a young man, who was not in the picture, said, “I don’t like that.” I smiled and pointed to Didier. “I have permission,” I said. “He is my permission.”

-11.660117

27.457647